The question isn’t “if” but “how” to replace Yallourn Power Station – and others – with renewable energy generation, Paul Treasure writes.

NUMEROUS COLUMN INCHES have – and continue to be – devoted to the impending shutdown of the Liddell Power Station in NSW and how the grid will cope without it.

Closer to home, the supposed crisis that closing the Yallourn Power Station will precipitate – and who or what policies may be to blame (or thank?) for bringing this forward – appears to be a growing preoccupation for some in the Murdoch press.

With the dubious honour of being Australia’s dirtiest power station, following the closure of Hazelwood, along with an increasingly patchy reliability record and challenges accessing coal going forward, the case for the closure of Yallourn Power Station is compelling. As with Liddell, none but the most ideologically driven (or those with a political narrative to perpetuate) are questioning "if" closure in the short to medium term is necessary. The "when" and "how" – particularly, what is to replace it – are more pressing.

While Yallourn has, over its lifetime, burned through a large chunk of our "carbon budget", it has also provided a number of benefits to the state. Victoria’s power grid was built around the large, synchronous generators of the Latrobe Valley, delivering not only large volumes of energy to the residents and industries of Melbourne and beyond, but also stability (frequency and voltage control) and reliable power capacity. Through construction and operation, it has also provided steady jobs for many in the Valley.

Despite a lack of policy certainty, renewable energy generation is taking up the slack of delivering energy to the grid, with the 3.5GW of projects under construction or completed nationwide in 2017 alone eclipsing Yallourn’s 1.5GW. This intermittent generation does, however, raise new challenges with increased requirements for peaking capacity and spinning reserve and contributes less to grid stability than traditional synchronous, "base-load" generators.

There may, however, be a replacement not so far from Yallourn that replaces its grid stability and firm capacity functions, while providing the peaking and reserve capacity that will be increasingly required going forward. And, of course, jobs.

In November last year, Australian National University (ANU) released a report on an ongoing study which identified 22,000 potential pumped hydro energy storage (PHES) sites around Australia, including 4,400 in Victoria. PHES accounts for 97 per cent of installed energy storage capacity worldwide, and requires an upper and lower reservoir — water is pumped up when the wind/sun are blowing/shining and let down when power is needed.

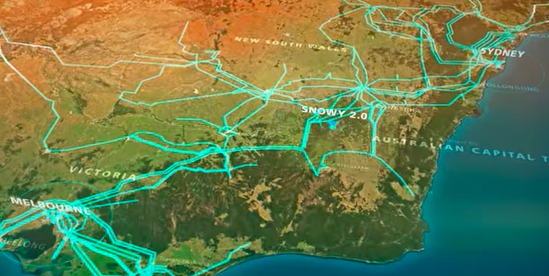

Many of the potential reservoir sites identified by the ANU report are relatively small and distant from the existing grid and work is currently ongoing to identify potential lower reservoir sites. There is, however, one site that appears to stand out from the pack and could rival or surpass the proposed Snowy 2.0 expansion in scale and value.

At an altitude of over 1,000 metres, the upper reservoir would be created off the north-west boundary of the Baw Baw National Park with a 600-metre dam, impounding approximately 30 gigalitres of water covering up to 140 hectares. Tunnels under the Baw Baw plateau would connect this new reservoir to the Thomson Dam approximately 15 kilometres to the east and 650 metres below. A two-gigawatt power plant (equivalent to the Snowy 2.0 proposal and 30 per cent larger than the existing Yallourn W generator) could be run at capacity continuously for up to 40 hours — sufficient to firm up much of the renewable capacity expected to be installed in Victoria over the next decade.

By comparison to Snowy 2.0, tunnelling (the major cost of that project) is reduced by almost 50 per cent. A new reservoir is required, unlike in the Snowy scheme, entailing a longer environmental approvals process. But using rock excavated from the head-race tunnel to build the dam wall should mean construction costs are not prohibitive. The key differentiator between the two, however, is likely to be in connecting to the existing grid.

Whereas the cost of integrating Snowy 2.0 has been estimated up to $4.5 billion, owing to its location adjacent to large existing peaking capacity (the existing Snowy scheme), the Baw Baw Power Plant would be 33km as the crow flies from the Victorian 500kV backbone and only 40km from Yallourn. Associated costs are, therefore, expected to be an order of less magnitude — the grid is designed for large, synchronous generators at this point. If planned well, the Baw Baw PHES could well provide a seamless transition to support the Victorian grid in the way Yallourn now does.

So next time the press or politicians infer that extending the life of our dirtiest power station is the only way to support the Victorian grid, provide Latrobe Valley jobs and keep downward pressure on energy prices, our response should perhaps be to turn the question around. The descendants of Sir John Monash – the visionary behind the Victorian grid as we know it – have objected to the use of his name by these groups to support extending the use of technology that no longer suits the times. We should likewise challenge our leaders to think as he did: consider how today’s technology can meet the needs of tomorrow and plan accordingly.

Paul Treasure is an engineer and project manager with over ten years of experience developing and building large-scale wind and solar farms in Australia.

This article was originally published on Peter Gardner's blog under the title 'A Gippsland Pumped Hydro Alternative to Snowy 2.0 by Paul Treasure' on April 8 2018. Read the original article.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.