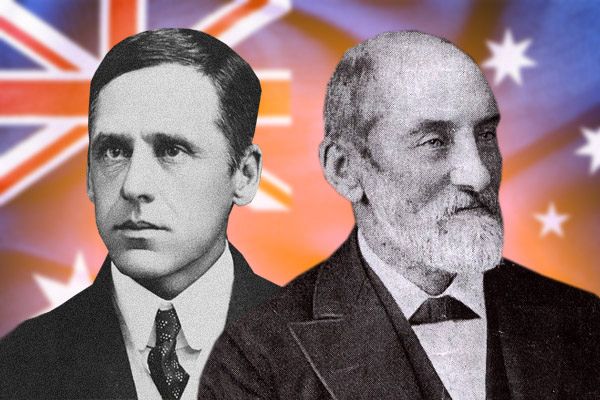

History editor Dr Glenn Davies explores the contest of popularity between Advance Australia Fair and Waltzing Matilda.

NOT SO LONG AGO, on 19 April 1984, Australia finally got a national anthem of our own, when Bob Hawke’s Labor Government replaced the use of the British anthem God Save the Queen with Advance Australia Fair.

19 April is the 36th anniversary of the adoption of Advance Australia Fair as our national anthem for the second time. 19 April 2018 began the four-day event of the first Winton’s Way Out West Fest celebrating the rebirth of the Waltzing Matilda Centre and the 125th Waltzing Matilda Day.

Advance Australia Fair had first been adopted by the Whitlam Government in 1974 after it was chosen by 51.4% of Australians in a survey of 60,000, defeating Waltzing Matilda, chosen by 19.6% of those polled.

But the decision did not stick. A change of government brought God Save the Queen back into use.

In May 1977, the Fraser Liberal Government had the Australian Electoral Office conduct a poll, or plebiscite for the national anthem in conjunction with a referendum. Advance Australia Fair was the clear favourite with 43.3% of the vote, ahead of Waltzing Matilda with 28.3%, and God Save the Queen at 18.8%, and The Song of Australia on 9.6%. Yet even that overwhelming vote did not see an Australian anthem restored until 19 April 1984.

Waltzing Matilda is Australia’s best-known bush ballad and has been described as the country’s unofficial anthem, or national song.

On 6 April 1895, Waltzing Matilda was performed publicly for the first time in the dining room of the original North Gregory Hotel, Winton. The current brick incarnation opened in 1955, after three previous versions burnt down.

Winton today is a flyspeck on the vast Mitchell Grass Downs, 1,400 kilometres north-west of Brisbane and almost two hours’ drive from Longreach. In 2012, Winton organised the inaugural Waltzing Matilda Day on 6 April, the anniversary of its first performance in 1895.

At the beginning of the 1890s, a long economic boom that had sustained four decades of rising prosperity ended abruptly. This precipitated a series of great strikes in which trade unions were defeated culminating in the violent 1894 shearers’ strike in north-west Queensland. Striking shearers armed themselves, woolsheds were burnt, men guarding property were fired on, and non-union workers were assaulted. Police and troops were sent in. Martial law was re-introduced in Winton.

In September 1894, on Dagworth Station, north-west of Winton, striking shearers fired their rifles and pistols in the air, setting fire to the woolshed. The owner of the homestead and three policemen gave chase to a man named Samuel Hoffmeister, also known as “Frenchy”. Rather than be captured, Hoffmeister shot and killed himself at the Combo Waterhole. It has been widely accepted that the lyrics of Waltzing Matilda are based on the incident.

Poet, lawyer and journalist Andrew “Banjo” Paterson started it all when he travelled up from Sydney in 1895 to meet his fiancée of six years, Sarah Riley, whose family owned property in the district. In Winton, they ran into Christina Macpherson, an old school friend of Sarah’s, whose brothers owned nearby Dagworth Station. Christina’s father had convinced his daughters to travel to Winton after the death of their mother only weeks before.

The Paterson, Riley, Macpherson group travelled together from Winton to Dagworth.

Over the ensuing summer, a firm friendship grew between the group and Christina’s brothers, who had such a different life from Paterson.

As a squatter, Christina’s brother, Bob Macpherson, had most of the stories to tell. Paterson rode with him across the property, hearing tales of shearers’ strikes, union upheaval and the burning of shearing sheds just eight months before on the very ground they travelled. There was even a gun battle between Bob’s station hands and 16 shearers resulting in the loss of life, lambs and public order. Shearers had set fire to buildings and public feeling against employer and employee had been high.

Bob told Paterson of how he had accompanied a police constable that same day of the gun battle to find the culprits. Instead, they found the body of shearer Samuel Hoffmeister, lying near a waterhole, killed from a self-inflicted bullet wound.

The evening was a good opportunity for the group to get together and amuse each other with their talents. One evening, Christina Macpherson played a march called The Craigielee that she had heard at the Warrnambool Races near her home in country Victoria the year before. Paterson was inspired to put words to it and penned the now-famous words of Waltzing Matilda to amuse the group.

Days later, back at the Riley house in Winton, the group made their changes to the song and decided to perform it publicly at the North Gregory Hotel on 6 April 1895.

The ballad of Waltzing Matilda was born.

Many details are contested, but by the time Banjo left town he apparently was no longer engaged and Christina and Sarah were not speaking. He barely spoke of the song again.

Waltzing Matilda tells of a swagman waiting for his billy to boil beside a billabong and singing to himself as he does so. A sheep strays into the scene and the swagman grabs it for his tucker. A squatter, presumably the sheep’s owner and three policemen descend on the hapless swagman, but rather than surrender he jumps into the billabong and drowns.

The song quickly became popular locally and soldiers sang it in the Boer War, spreading it across state boundaries when they returned home. But it was as an advertising ploy for Billy Tea that embedded Waltzing Matilda in national mythology.

From the 1890s, the Billy Tea packet showed a swagman drinking his billy tea and conversing with a kangaroo carrying a swag and billy. In 1902, James Inglis and Co, who imported Billy Tea, acquired the lyrics but wanted them to be rejigged. The association in the Waltzing Matilda lyrics between the billy and death needed to be repositioned for a beverage marketed as a refreshing and uplifting brew.

The task of commercialism the song fell to Marie Cowan, the wife of Inglis’s manager. Cowan added the word “jolly” to the opening line and injected “billy” into the chorus, ensuring its repetition and its association with the product. She also capitalised the ‘B’ and added inverted commas:

‘And he sang as he watched and waited till his “Billy” boiled,

You’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me.’

The sheet music provided with the tea acknowledged Paterson as author and Cowan as the arranger of the music. The song, the tea and the billy came together to firmly secure the popularity of all three.

The billy was democratic, used by men and women, rich and poor, black and white, workers and leisure-seekers, but its association with the bushmen and in particular the swagman gave it national meaning. Like the swagman, the billy was dependable, resourceful, practical and egalitarian, even anti-authoritarian.

In the upsurge of national sentiment that marked the last two decades of the 19th century, artists and writers identified the bush as the real Australia and the bushman as the real Australian. It was in this context that the billy could stand for the nation.

In the stories and poems of Henry Lawson and “Banjo” Paterson, in the art of the Heidelberg School and in bush ballads and folk songs, somewhere there was nearly always a billy, an almost obligatory motif to establish the authenticity of the scene.

Henry Lawson’s first major collection in 1896 was called ‘While the Billy Boils’.

The boiling billy was usually a call to yarn and chat, however in Henry Lawson’s 1891 ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’, it was a call to arms:

An' Freedom’s on the wallaby...

She’ll knock the tyrants silly,

She’s going to light another fire

And boil another billy.

We’ll make the tyrants feel the sting

Of those that they would throttle;

They needn’t say the fault is ours

If blood should stain the wattle.

For Lawson, the billy stood for the rebellion of workers against the bosses and so it symbolised the push for democracy and republicanism that marked late-19th-century Australian bush nationalism. Lawson was giving these conversations “while the billy boiled” credit for the very creation of Australia as a nation.

The Waltzing Matilda Centre was built in Winton in 1998 after celebrations to make the song’s centenary. After battling years of drought, the western Queensland town had its landmark Waltzing Matilda Centre gutted by fire in 2015, leaving the community devastated.

In 2018, Matilda resumed her waltz with the official reopening of the $22 million iconic Waltzing Matilda Centre with one of the biggest inland music and culture festivals ever held in Queensland. Winton’s Way Out West Fest attracted 8,000 people to the tiny town where the population is normally a tenth of that, with online news coverage of the opening seen by more than 70 million people and generating 4.5 million social media views. Governor-General Sir Peter Cosgrove and Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk were part of the star-studded weekend of festivities, along with The Living End, John Williamson, Jessica Mauboy and many others.

Even though there may be an ongoing contest of popularity between our national song and our national anthem, they both reflect our national streak of independence.

For Henry Lawson, the boiling billy was a call to arms, whereas for “Banjo” Paterson the billy represented the dependable, resourceful, practical and egalitarian, even anti-authoritarian nature of the Australian people.

It seems unimaginable today that Australia did not have its own national anthem until the 1980s. It will seem unimaginable to future generations that we delayed adopting our own Head of State for so long after coming of age as a nation.

It will, likewise, take a second attempt to cut Australia’s final Constitutional link to the British monarchy, to reflect the full independence that Australians already feel in their hearts.

The question is not whether this will happen, but when.

You can follow history editor Dr Glenn Davies Glenn on Twitter @DrGlennDavies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.