It is time we recognise that even as they were serving in the Imperial Defence Force, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people were being massacred in a domestic war of colonisation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island activists have established a tradition of commemorating the Frontier Wars on Anzac Day despite the reluctance of official authorities.

Every year, they march at the tail of the Anzac Parade holding the banner 'Lest We Forget The Frontier Wars' and a list of the dates, places and numbers of victims persecuted during the killing times.

The commemoration of the Frontier Wars on Anzac Day is an intervention in the collective memory to remind the nation that Australians have witnessed war well before the First World War. The war that made modern Australia started in 1788 when the First Fleet of British ships landed in modern-day Sydney.

In Canberra, where the national Anzac Day services are held, the tradition of commemorating the Frontier Wars began in 2011 when members of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, led by Mick Thorpe, marched with their commemorative banners. Thorpe was carrying both the weapons of the traditional warrior who fought against the European invaders and the medals of his grandfather who died on the Somme in 1918. He embodied the multidimensional nature of the Aboriginal history of war and the continuity between past and present.

Despite years of advocacy and debates, the Frontier Wars are still excluded from official rituals of war commemoration and from the halls of the Australian War Memorial. Former director of the Australian War Memorial Brendan Nelson insisted that legalistically the Frontier Wars were not a war, but the historian Henry Reynolds presents a compelling examination of history that illuminates why and how they are, in fact, forgotten wars.

The organisers of national Anzac Day services have at best tolerated the memory intervention made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island activists, but have never accepted or welcomed it. Every year in Canberra, the contingent of people marching in memory of the Frontier Wars is met by a line of police officers, which separates the contingents that are given permission to march in the Anzac Parade from the uninvited and unwelcomed group commemorating the Frontier Wars. The activists lay their commemorative wreaths in front of the police, which is a symbolic reminder of police brutality against Indigenous people, as well as of the forceful exclusion of the Frontier Wars from war memory on Australia.

This year, Anzac Day was celebrated digitally and activists could not make their usual intervention in Australia’s collective memory of war. But this did not make Anzac Day 2020 uncontested.

Indigenous activists, people and allies have used social media to intervene in war memory. Many have used the hashtag, #FrontierWars, on Twitter and Instagram to share words and images that keep alive anti-colonial resistance and the memory of the Frontier Wars.

Some have hosted digital ceremonies. For example, the anti-war, anti-militarism group, Wage Peace, organised a Zoom meeting on the 24 April to commemorate the Frontier Wars with rituals, interviews with sovereign people and short video clips. The meeting was recorded and is available on Facebook.

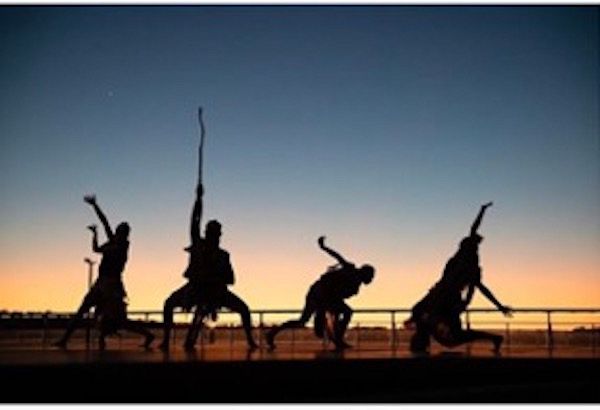

Leading Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander performing company Bangarra is also digitally commemorating the Frontier Wars. They are touring online with their show, Bennelong, a choreography in memory of the Aboriginal warrior Bennelong, who was kidnapped under the orders of King George III in 1789 and taken to London to be shown off as a curiosity.

Recognition and acknowledgement of the Frontier Wars between Indigenous peoples and European colonisers and their inclusion in the national memory of war is an important step towards reconciliation and national unity. Setting the historical records right and naming the violence that has been perpetrated are fundamental to heal the national trauma and move forward.

Indigenous soldiers have progressively been included in Anzac Day commemorations, but national war memory cannot celebrate their contribution to modern warfare without also acknowledging that, at the same time that these soldiers were serving the Australian nation in the Imperial Defence Force, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people were being massacred in a domestic war of colonisation.

Dr Federica Caso's works as a teaching assistant at the University of Queensland and her expertise is in militarisation and war memory in liberal societies. You can follow her on Twitter @Federica_Caso.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.