After nine years of Coalition failure, the Albanese Government has an opportunity to lead the world on alternative affordable housing, as Alan Austin reports.

*Also listen to the audio version of this article on Spotify HERE.

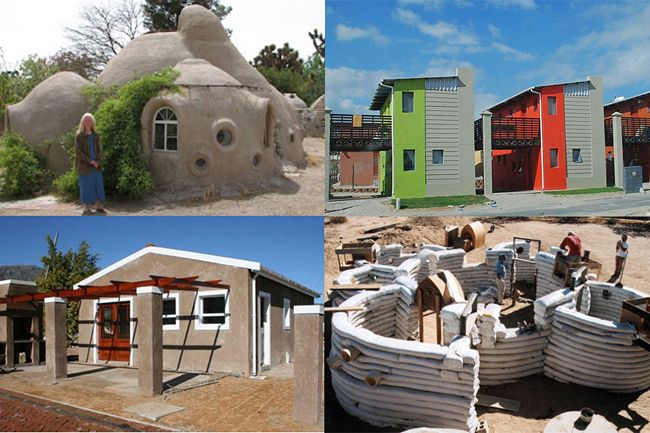

THE FOUR HOUSES shown above are completely different in size, style, construction and location, but have several things in common. They are environmentally friendly, extremely cheap to build and fast to construct. Why? Because they are all made of bags filled with sand.

Many countries with urgent social housing needs are constructing low-cost houses using a range of alternative building materials. The four sandbag dwellings above are, clockwise from top left, in Veracruz, Mexico, Capetown, South Africa, Ahwaz, Iran and Durban, South Africa.

Other construction materials, besides bags filled with earth or sand, include bamboo, plant fibre board, synthetic concrete, papercrete, dune sand cement, rammed earth, sawdust pykrete, old shipping containers and plentiful recycled rubber tyres, reclaimed timber and glass and plastic containers.

Several countries are encouraging alternative architecture and engineering, including earth sheltering and sustainable landscaping.

The home below is made of used plastic bottles and other recycled waste. This is one of many innovations of Earthship Biotecture, based in Tres Piedras, New Mexico, USA. These dwellings feature solar and wind power for heating, cooling and other energy needs plus self-contained sewage treatment.

Australia lagging in global innovation

Australians must now face the challenge of alternative housing with more urgency than has been shown in the past. Among the shameful legacies of having had Coalition governments for 20 of the last 27 years are high rates of homelessness of people in poverty and low scores on innovation.

The annual Global Innovation Index is published by the Swiss-based World Intellectual Property Organisation, an agency that promotes innovation and creativity for a sustainable future. In the first two years of the recently-departed Coalition Government’s management of Australia’s economy, 2014 and 2015, Australia’s global ranking was 17th. Not brilliant, but not bad. That’s out of 132 nations, of which the leaders back then were Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Finland.

It has been downhill from there with the ranking slipping to 19th in 2016, 20th in 2018, 23rd in 2020 and eventually 25th in 2021 and 2022. Leaders last year were Switzerland, the USA, Sweden and the UK.

So the pressure is on the Albanese Government to get Australia back up among the leaders. Housing is a critical place to start. Here’s why.

Failing also on homelessness

Last month, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that 122,500 Australians were homeless on Census night in August 2021. That was 480 for every 100,000 in the population. This was higher than at the 2016 Census, when the number was 116,400, but slightly better than the 2016 rate of 500 people for every 100,000.

Georgia Chapman, ABS head of homelessness statistics, said that measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in 2021 made the situation look better than it actually was:

“During the 2021 Census, we saw fewer people sleeping rough in improvised dwellings, tents or sleeping out, and fewer people living in severely crowded dwellings and staying temporarily with other households. However, we saw more people living in supported accommodation for the homeless, boarding houses and other temporary lodgings, such as a hotel or motel.”

Men comprised the majority of the homeless in 2021, with 550 in every 100,000 Australian males having nowhere to live. Homeless women numbered 420 in every 100,000.

Fortunately, between 2016 and 2021, the homelessness rate decreased in all age groups except those under 18.

In 2021, 24,930 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were estimated to be homeless. That’s more than one in five of all homeless Australians.

The Census revealed that three in five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were living in “severely” crowded dwellings, almost one in five were in supported accommodation and nearly one in ten were living in improvised dwellings, tents or sleeping out.

Thus the remote Indigenous communities are where alternative housing solutions will be most strategic.

Australia’s dismal global ranking

World Population Review (WPR) records the number of homeless people for 35 advanced member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Japan currently has the best record of housing its citizens, despite having the third-highest population, after the USA and Mexico. Second best is South Korea, also in the East Asian region, and then Switzerland. The two worst nations for homelessness, surprisingly perhaps, given their wealth and long cold winters, are the United Kingdom and France. See chart, below.

Australia is currently assessed by the WPR as having 380 homeless people per 100,000 population, which is below the ABS estimate for 2021. Whether this reflects a substantial improvement since then or a different methodology is not clear. Possibly, both factors apply here.

What is certainly clear from the WPR’s comparative data is that Australia ranks an appalling 32nd out of the 35, with its 380 more than double the OECD average of 188.

Can the relatively new Labor Government collaborate effectively with the 16 Greens and seven teal Independents in Australia’s fresh Senate and House of Representatives to fix this?

If so, we shall monitor progress with optimism. After all, Australia has plenty of sand.

*This article is also available on audio here:

Alan Austin is an Independent Australia columnist and freelance journalist. You can follow him on Twitter @alanaustin001.

Related Articles

- Population growth fuelling the housing crisis fire

- Jobs and housing: People with disabilities need a fair go

- A new resolution could solve the housing emergency in Europe

- The unpredictable fall of housing prices

- Coalition’s hands-off housing policy points to 2019 election defeat

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.