Rising house prices may sting homebuyers, but the Reserve Bank’s latest research shows they actually stimulate growth — boosting GDP, spending, investment and employment in the medium term. Stephen Koukoulas reports.

WITH THE ECONOMIC and policy debate continuing to be dominated by house prices, housing affordability, interest rates, dwelling construction, housing supply and demand issues, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has released research that shows how rising house prices actually help the economy, at least in the medium term.

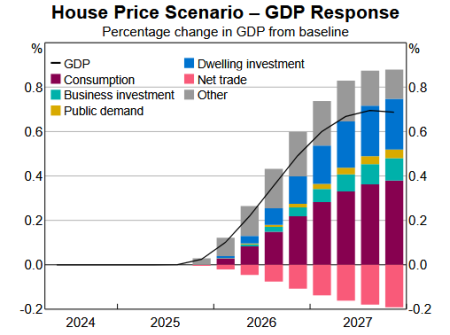

The November RBA Statement on Monetary Policy included an update on some of the Bank’s earlier research that shows how the wealth effect on households from higher house prices impacts the economy. In simple terms, the RBA found that rising house prices boost consumption, business investment, public demand and dwelling investment, with some moderate, generally positive spill over to other parts of the economy.

The bottom line of the research found that for a 10 per cent increase in house prices, the level of GDP is boosted by 0.7 per cent relative to the central forecast.

It found that the boost to GDP growth flows through to higher inflation, adding around 0.25 percentage points to trimmed mean inflation over the medium term.

This should come as no surprise, with much of Australia’s prosperity, in absolute terms and relative to almost all other countries, linked to the growth in wealth, including in superannuation savings and also in housing.

It must be noted and emphasised that the RBA does not directly target house prices with its interest rate settings. It never has and never will.

It does, nonetheless, have a deep interest in housing from a number of perspectives.

As hinted above, it looks at the pressures and risks to economic growth and inflation from material swings in house prices, both up and down. Note that sharp falls in house prices undermine wealth, household spending, lower inflation and, as a result, lower interest rates, based on the RBA’s modelling. This is the reverse effect of rising house prices.

Financial stability matters

The RBA has a keen interest in issues of financial stability from house price cycles, bank and financial institution prudence in mortgage lending and the household sector’s financial management of mortgages.

If banks and financial institutions are too slack (or strict) with lending, the RBA will note the macroeconomic effects of such policies and will liaise with other regulators to correct any risk to stability that is at risk of escalating from the financial sector.

Financial instability sparked by questionable adherence to lending standards, for example, would see the RBA hold monetary policy tighter as a counterpoint. It would do so until these problems are corrected by the financial institutions and regulators.

As the recent press conference after the “on hold” interest rate decision, RBA Governor Michele Bullock was asked about the so-called credit quality of the mortgage market and the household sector’s financial position.

Bullock noted that on the current readings, there were no material signs of any significant imbalances. Banks were well capitalised, credit was flowing to creditworthy borrowers, provisions for bad debts were low and the financial systems was functioning well. The household sector was in a strong financial position.

In other words, the sound functioning of the financial system and solid balance sheet position of the household sector were not a material issue for the RBA and the setting of interest rates.

This is good news.

In large part, the persistence of stability and security in the financial system helps to explain the buoyancy in the financial position of the banking sector, including the stunningly strong increase in their share prices in recent years.

Longer-run effects of rising house prices

It should be noted that in the footnotes from the RBA research on the effects of rising house prices, it found:

‘Under this scenario [of rising house prices], the path for the cash rate should shift up relative to the baseline. Under this scenario, the increase in demand for housing assets would be unwound (likely beyond the forecast period), so the effect on the level of GDP, real house prices and inflation is only temporary.’

In other words, the very long run effect is broadly neutral as higher growth, higher inflation lead to higher interest rates, which work to slow the economy with the usual lags.

All of which points to changing house prices as part of the swing element in the business cycle. Rising house prices are good for the economy, including employment, over the short to medium term. In other words, when the economy is relatively weak, as it is now, a period of rising house prices can help to underpin economic activity, albeit with some upside inflation.

There are a myriad of other economic issues related to housing — construction costs, the availability of suitably skilled labour, competition or a substitution with the non-residential construction sector are a few.

Suffice to say, housing is a dominant issue for the Australian economy and will have an impact, albeit indirect or not fully acknowledged, on policy settings.

Stephen Koukoulas is one of Australia’s most respected economists, a past chief economist of Citibank and senior economic advisor to an Australian Prime Minister. You can follow Stephen on Twitter/X @TheKouk.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles

- RBA's interest rate cut a double-edged sword

- Interest rate changes don’t always sway voters

- Government should stop letting Reserve Bank govern Australia

- Some very basic questions for the Reserve Bank of Australia

- RBA deputy governor hits a few prophets for six