Robodebt was a massive failure of public policy that might not have proceeded if those who helped enable it had pushed back on a questionable scheme they knew had significant flaws, writes Paul Begley.

FINN PRATT knows what it’s like to be handed a poisoned chalice.

Along with the late John Kovacic and other senior public servants, Pratt was a deputy secretary in the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations during the heady days of John Howard’s Workplace Relations Amendment (Work Choices) Act 2005'.

It created a minefield and Pratt did a serviceable job in helping to steer a path that minimised detonations until the Howard Government was despatched to history by voters in 2007.

Returning to his office as secretary of the Department of Social Services (DSS) after the Christmas break in January 2015, Pratt was about to be handed another poisoned chalice. A new DSS minister, Scott Morrison, had been appointed by Malcolm Turnbull.

According to Annika Smethurst’s biographical account of Morrison’s political rise in her book The Accidental Prime Minister, social services was a portfolio Morrison was determined to use to boost his prospects for an office more aligned with his ambitions.

Evidence put to the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme included Pratt’s handwritten notes of the fateful Morrison meeting. The notes included references to the term “welfare cop” — Morrison spoke in the media about a "strong welfare cop on the beat".

The idea was to generate savings in excess of a billion dollars for the 2015 Budget, which coincidentally would operate as a tough-guy credential for Morrison’s successful aspiration to replace Treasurer Joe Hockey, whose ill-starred 2014 Budget had wounded him politically.

DSS existed as a policy agency charged with designing programs to assist citizens who were undertaking study, suffering ill health, undergoing unemployment or drawing an age pension after a lifetime in the workforce.

After Morrison’s February 2015 meeting with Pratt, the safety net agency increasingly focused on punitive mechanisms to remedy recipient fraud and stop welfare cheats in their tracks.

If Australia’s social security system could be imagined as an aircraft dropping food and other necessities of life to assist Australian citizens in times of need, Morrison’s “cop on the beat” configuration transformed the aircraft into a fighter plane more suited to firing rockets at them than dropping off life’s necessities.

Pratt had plenty on his plate when Morrison ventilated this transformational idea, so he handed carriage of it to deputy secretary Serena Wilson, an officer in whom he had great confidence, according to his evidence at the Royal Commission.

Watching the live-streamed Robodebt hearing over the past few months has been a stark reminder that holding a public service job carries with it heavy responsibilities and accountabilities.

That’s particularly true at the secretary and deputy secretary level, but even for those down the pecking order, Justin Greggery KC and Angus Scott KC have been there as Counsel Assisting the Commission to remind these public servants that they signed up to a code of conduct obliging them to use their expertise to give frank and fearless advice in the interests of their customers: the Australian people.

Evidence given by middle-ranking public servants below the DSS deputy secretary level shows in many cases that they were caught in a dilemma. They were in receipt of enough information to make judgements about the impact of automated debt collection outcomes to which they were contributing while also believing there was a limit to how much they could push back against the grossly harmful implementation issues they encountered without stepping over an entrenched hierarchical line.

With the Royal Commission looking at Robodebt policy innovations that carried with them the reversal of onus – eventually determined to be illegal – one group of witnesses was found to have stricter levels of accountability: because they had law degrees. Greggery and Scott were there to remind these witnesses of that fact.

Among that group were those with practising certificates. In addition to their obligations as public servants, they were under a particular obligation to be mindful of their responsibilities in terms of offering advice in accordance with their professional standing. Those without practising certificates could simply say they remember little of what they learned when studying law at university — making the point that they were public servants, not lawyers.

Former Human Services Minister Alan Tudge fell, perhaps unwittingly, into that group. He was keen to explain that he had never practised law and had, for example, no recollection of distinguished constitutional law silk Peter Hanks KC, despite having read his textbook at university.

Hanks had given a timely paper at an administrative law conference attended by a number of Department of Human Services (DHS) luminaries. The paper was scathing of Robodebt and questioned its lawfulness on a number of counts, but it was not brought to the attention of Tudge — according to his evidence under oath.

Among the practising lawyers – with titles such as "general counsel" and "chief counsel" – were those held to standards which didn't favour them getting away with answers along the lines of, I had no reason to doubt the advice I was receiving.

Commissioner Catherine Holmes was impatient with that type of nonsense. She asked these lawyers if they had ever thought of asking themselves whether the advice they were receiving made sense legally by using their own judgement.

She asked DHS Chief Counsel Annette Musolino directly:

“Did you ever talk to your equivalent in the DSS division?”

Higher up the chain of command at the deputy secretary and secretary level, the refrain most relied on was that the matter was being dealt with in the other department.

Musolino described her department, DHS, as relatively new and immature. DSS Secretary Pratt gave evidence that he largely lost track of the Online Compliance Intervention (OCI) program, with it having passed to DHS and with his attention focused on more pressing matters such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). He accepted the proposition that the OCI program had become a headache but told the Royal Commission that “it was someone else’s headache”.

To her credit, Pratt’s OCI lieutenant Serena Wilson admitted to a failure of courage in not pushing back on a questionable policy that had the endorsement of an impatient minister.

Despite advice that without new legislation the program was not on a sound legal footing, Wilson regretted doing nothing to stop its progress and confessed as much — the policy had momentum and possibly would not proceed if legal advice were required before it could be put to Cabinet as a budget savings measure.

She would have been mindful that its patron, Scott Morrison, was an ambitious politician with a reputation for responding with belligerence to anything that sounded like "no, minister".

Courageous agency heads such as Professor Gillian Triggs, former head of the Australian Human Rights Commission, had been publicly threatened and humiliated by Morrison — a recollection that would likely have had a chilling effect on anyone in the department.

DHS Secretary at the time, Kathryn Campbell, did little to assist the situation with her apparent readiness to endorse the Morrison policy, come what may. That was still evident in her haughtiness at the Royal Commission when a degree of contrition would have been more advisable.

Greggery put it to her that Robodebt was a “massive failure of public policy”. Campbell would have done well to have accepted that phrase but came back with a pedantic modification by proposing it was merely a “significant” failure — a shade of meaning that would have been lost on the many thousands of Australians who have suffered lasting trauma under the OCI scheme, including the family members of those who suicided.

By the time it came to pass that the program was up and running in 2016-17, Secretary Pratt was preoccupied with other matters.

The policy might have come to nothing had legislation been required, but Royal Commission witnesses were hard-pressed to explain how a DSS minute in late February 2015 stating that legal advice was required before the policy could go to Cabinet had mysteriously changed by early March to a minute which omitted mention of that obstacle. Accordingly, Morrison was free to take the matter to Cabinet on the strength of the March minute.

Apart from Wilson, the late Malisa Golightly was charged with OCI delivery as Kathryn Campbell’s DHS lieutenant. Using the fighter plane analogy, if Morrison had fired the first rocket, Golightly appeared keen to ensure that his punitive model prevailed and that any questions about its legitimacy were taken as traitorous.

Long-time DHS head of communications Hank Jongen made an attempt to raise some of the issues informally with Golightly about what he was observing, but he gave evidence that she immediately became heated and shut him down.

Similarly, Karen Harfield, DHS' customer compliance general manager, gave evidence that she had raised her concerns at a meeting with Golightly early in 2017 but was angrily reminded of her relatively low rank after suggesting they needed a major response. Golightly instructed her to restrict her focus to doing her job by delivering the program.

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote a book in 1963 about the humdrum exercise of the machinery of public administration. In coining the phrase 'the banality of evil', Arendt illustrated the ordinariness of the behaviour of administrative enablers.

It’s now 60 years since Arendt first used that phrase, yet the passing of time has not impeded the profusion of banality that has been on show in Brisbane at the Robodebt Royal Commission.

Paul Begley has worked for many years in public affairs roles, until recently as General Manager of Government and Media Relations with the Australian HR Institute. You can follow Paul on Twitter @yelgeb.

Related Articles

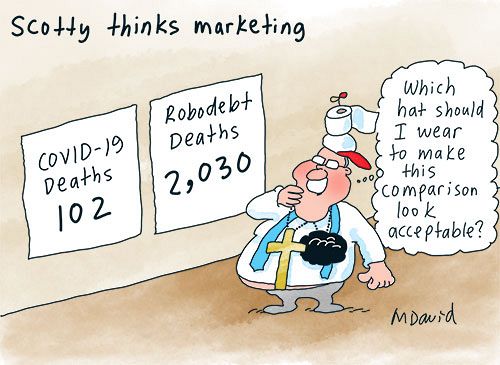

- CARTOONS: Robodebt rat pack is facing facts at the RC

- Alan Tudge's Robodebt RC performance akin to pulling teeth

- Robodebt's privileged perpetrators shamefully punished the poor

- Scotty the Welfare Cop and his Robodebt Royal Commission copout

- EDITORIAL: Scotty the Welfare Cop and his Robodebt Royal Commission copout

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.