The monopolisation of media isn't just undemocratic — it enables criminal economies to flourish behind a façade of control, writes Nick Potter.

WHEN A GOVERNMENT declares that it “solely controls” the media, this is not just political bravado; it is a profound signal.

Beneath the rhetorical flourish lies the architecture of organised capture: the capture of narrative, the capture of oversight, the capture of commerce. In jurisdictions where the executive, judiciary and press become enmeshed under a single authority, the conditions are ripe for illicit economies to flourish behind a façade of legitimacy.

Monopolising information

At its most basic, the power to control media means the power to suppress scrutiny, shape public perception and protect – or cloak – entire networks of illicit trade.

When the press cannot investigate, when the judiciary is unfree and when law enforcement operates without transparent oversight, crimes are not merely committed — they become structural. The story is never told, victims remain invisible and the perpetrators walk in plain sight under the cover of officialness.

But let’s be clear: this doesn’t mean every state with strong media controls is criminalised. Nor does it mean all trade behind closed doors is automatically illegal. What it does mean is that the ideal conditions for grey-zone industry are created.

The industries that thrive

It is useful to see what kinds of trade multiply under such conditions, for example:

Resource theft and smuggling

In states where media is tightly controlled, illegal mining, timber logging, oil diversion or mineral expropriation can proceed with near-impunity. When the press cannot report on environmental devastation or corruption, activists are silenced — and the commodity flows remain hidden.

Human trafficking and forced labour

Victims of forced labour, modern slavery or human trafficking are rendered invisible when investigative journalism is muzzled. In this context, entire fleets of ships, domestic-worker abuse, or prison-labour systems can hide behind a wall of information control.

Narcotics and chemical precursors

When the state controls the “fight against drugs”, it can simultaneously run or permit drug corridors while broadcasting “success” to the public. Without independent oversight, the line between law enforcement and racketeering blurs.

Arms trade and militia funding

State-run companies can sell weapons to embargoed regimes, fund paramilitaries or channel money through front companies. Controlled media ensures the sales happen quietly, the profits flow unseen and the official record remains clean.

Organ trade and medical exploitation

When medical systems, prisons or detention camps operate out of sight, unlawful medical harvesting, organ trade or experimentation can evolve. With no independent press to expose anomalies, the victims vanish into the system.

Digital surveillance and data harvesting

In our age, the capture of information itself is an illicit trade. When media is state-monopolised, surveillance programmes, data mining of citizens and intelligence exports become part of a hidden economy.

Money-laundering and front companies

With media under state control, whistle-blower exposés are rare, regulatory bodies are weak and shell companies proliferate. The narrative monopoly shields large-scale laundering and the trafficking of illicit funds.

The mechanism of profit

How exactly does media control translate into profit? It follows a four-step conversion:

- Narrative monopoly: If the story doesn’t exist, the crime doesn’t exist in the public’s mind.

- Selective exposure: From time to time, a “public trial” is held – almost as theatre – not to address systemic corruption, but to reinforce the legitimacy of the system.

- Propaganda feedback: With repeated messaging, public trust in the authority grows and dissent shrinks; the informed citizen-voter dwindles.

- Rent extraction: Officials, cronies and state actors extract financial rents from illicit trades, while the system presents stability, not chaos.

These dynamics coalesce into a model of competitive authoritarianism — the system appears democratic, complete with elections and media, yet the pillars of separation are hollowed out.

Legal and global implications

Under international law and global norms, such conditions may implicate states or actors in:

- corruption, as defined in the United Nations Convention against Corruption (2003);

- complicity in crimes against humanity, particularly if forced labour or trafficking becomes systemic; and

- violations of press freedom, such as Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Yet enforcement is extraordinarily difficult, especially when the judiciary, police and media are aligned with or captured by the executive. Transparency disappears, oversight disappears, and the state becomes both arbiter and participant.

What can check this power?

It’s easy to despair, but tools to counter this pattern exist as follows:

- Whistle-blower protection: Safe harbours for courageous journalists and insiders are vital.

- Open-source intelligence (OSINT): Satellite imagery, trade-data leaks and financial-flow trackers all offer independent verification.

- International pressure and sanctions: Naming and shaming, combined with targeted economic measures, can disrupt captured systems.

- Public digital literacy: Citizens who recognise propaganda, misinformation and information monopolies reclaim power.

Why this matters for Australia

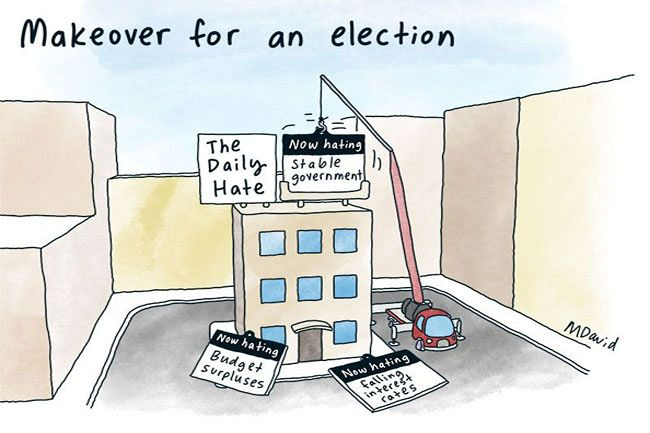

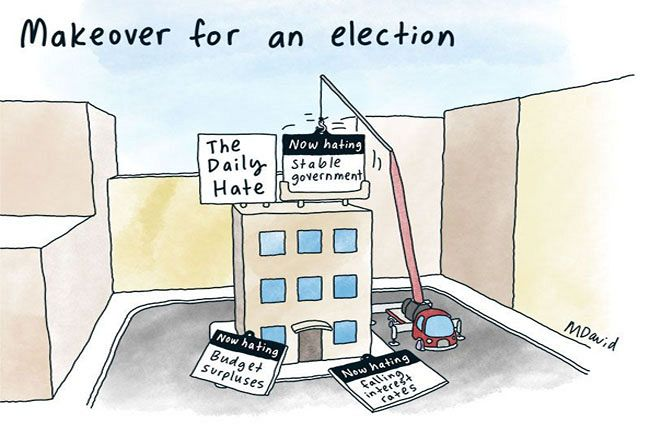

Although Australia is regarded as a strong democracy, global turbulence teaches us the importance of vigilance.

As media ownership consolidates, as surveillance expands and as executive power grows, the separation of powers and independence of press and courts are not guaranteed. When a system of power assumes the right to control the narrative, the question becomes: what is happening in the blind spot?

The lesson, then, is this: The control of media is not simply an information issue — it is a question of economics, justice, human rights and democracy.

When one authority controls the story, the story ends up serving the authority.

Nick Potter is a research and development technician and writer based in Melbourne.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.