Today, 8 September 2017, marks the 50th anniversary of the "Big March" from the University of Queensland. The 1967 protest initiated many years of direct action for a generation of young Queenslanders, reports history editor Dr Glenn Davies.

BRISBANE HAS a long history of protest activity. In 1912, during the Brisbane General Strike, more than 25,000 workers – many of who had taken to wearing red ribbons as a mark of solidarity – marched eight abreast in a procession three kilometres long from the Brisbane Trades Hall to Fortitude Valley and back, with more than 50,000 supporters watching from the sidelines. However, the ferocity of the police response on 2 February 1912 is still known as Black Friday.

The Red Flag Riots of 1918 and 1919 resulted from a federal ban on the display of the Red Flag. The Federal authorities were worried about the Russian Revolution of 1917 and had banned the display of the Red Flag. When Russian and British radicals attempted to march displaying the flag, they were attacked by police. On 24 March 1919, about 8,000 demonstrators and ex-servicemen marched from the city to the Russian Hall in Merivale Street where they clashed again with police. Up to 100 people were injured.

The rapid and widespread outbreak of social movement activity in the 1960s and 1970s resulted in many important reforms in Australian society and politics. This was seen, for example in the environment movement which, through militant grassroots action and community-based campaigning won many important victories right up to the 1990s, especially in the area of nature conservation.

In 1967, the Queensland premier was Joh Bjelke-Peterson, a Kingaroy peanut farmer with no understanding of the Westminster Parliamentary System of “Separation of Powers”. At the same time, the Queensland Police culture was distinct, with its own Special Branch. On 8 September 1967, a massive illegal march protesting involvement in the Vietnam War occurred after Queensland University students were refused a "permit to march". As many as 4,000 students marched from the University of Queensland into the city.

During the 1971 Springbok rugby tour, Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen declared a state of emergency over the anti-apartheid demonstration in Wickham Terrace. The police implemented their new powers vigorously.

In the 1970s and 1980s, street marches in Brisbane always seemed to begin in King George Square ― outside Brisbane City Hall. King George Square was the crucible for the city’s social disquiet and ferment, where thousands of protesters once risked the batons of Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s police force, over issues as diverse as the Vietnam War, the Springbok rugby tour, Aboriginal issues, nuclear disarmament and the right to protest. When the protesters went to walk out of the square, there would be hundreds and hundreds of police in military ranks to stop the marchers. As people tried to step out onto the roadway, they’d be strong-armed to the ground by police who would try to push them back into the square.

Following Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s decision in 1977 to expand uranium mining, an anti-uranium protest group was formed. In turn, Premier Bjelke-Petersen outlawed street marches, sparking a number of confrontations in the city. However, the "right to march" quickly became the main issue for both the marchers and the police.

On 4 September 1977, Bjelke-Petersen announced:

“Protest groups need not bother applying for permits to stage marches because they won‘t be granted ... that‘s government policy now."

He also announced that demonstrators refused a permit to march would no longer have the right of appeal to a magistrate. Now you could only appeal to the police commissioner. Political street marches, said Joh, were “a thing of the past”. This prompted widespread protests and protest marches against the removal of this fundamental civil right.

In 1978, Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s ban on all street marches led to violent clashes between police and protesters and the arrest of more than 2,000 people in 26 separate incidents. Tensions rose as the year progressed, with the biggest march of all being in December, when 346 people were arrested and packed like sardines into cells, often being denied a lawyer.

There was also a pacifist current to the campaign, that favoured disobedience but didn't want it to be militant. On April Fool’s Day 1978, student protesters from University of Queensland adopted a tactic of the No-March or Phantom March. They announced a campus to city march and marched to the edge of the campus where by then 1000 police had arrived and lined up to arrest the protestors once they left the campus. The police stood for over four hours waiting for a march. The organizers then called off the march.

These political frustrations with street march ban legislation in Queensland were the basis of the Australian folk and political music group Redgum’s 1978 single ‘Letter to B.J.' from their first album If You Don't Fight You Lose.

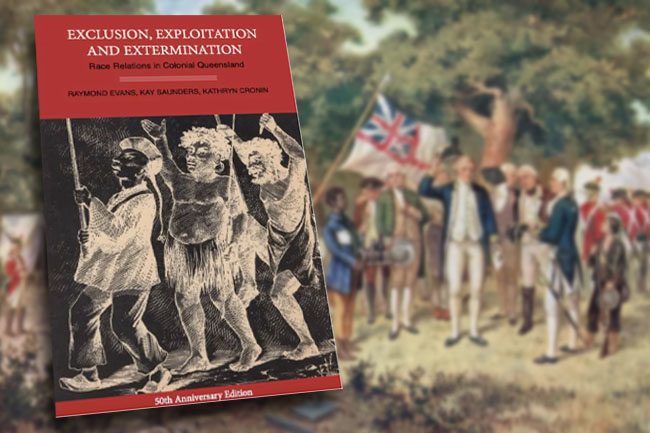

The 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games protests marked a historic turning point in the struggle for Aboriginal land rights in Queensland and across the country. 10,000 people set up tents in Musgrave Park, hundreds were arrested every day outside sporting venues across Brisbane. Soon after these massive protests, the Aborigines Act was repealed and the first land rights legislation started appearing around the country.

The Australian anti-nuclear movement emerged in the late 1970s in opposition to uranium mining, nuclear proliferation, the presence of U.S. bases and French atomic testing in the Pacific. Palm Sunday, the Sunday before Easter, is a traditional day of protest for peace. During the 1980s, Palm Sundays in Australia were the occasions for enormous anti-nuclear rallies all across the country.

The annual Palm Sunday rallies were organised by the People for Nuclear Disarmament, beginning in 1982 and reaching a peak in 1985. On Palm Sunday 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians participated in anti-nuclear rallies in the nation’s biggest cities. These rallies grew year by year.

In 1985, more than 300,000 people marched across Australia in Palm Sunday anti-nuclear rallies, demanding an end to Australia’s uranium mining and exports, abolishing nuclear weapons and creating a nuclear-free zone across the Pacific region. The biggest rally was in Sydney, where 170,000 people brought the city to a standstill. This was the high water mark for the anti-nuclear movement in Australia. As a result, the broadening of Australia’s nuclear program was halted.

Australia has seen some large protest marches in the past. At the first Vietnam War moratorium protest in May 1970, there were 70,000 people who marched in Melbourne and 20,000 in Sydney. In 1985, more than 350,000 people marched across Australia in Palm Sunday anti-nuclear rallies. The biggest rally was in Sydney, where 170,000 people brought the city to a standstill. In May 2000, there were 200,000 people who walked across Sydney Harbour Bridge in support of reconciliation.

The annual Brisbane Zombie Walk began in 2004 with just 300 participants. By 2005, it had grown to 1,500 people as word spread on the internet. In 2006, some Brisbane burghers were freaked out when a horde of zombies shambled down Adelaide Street at the same time as the official opening of the revamped King George Square. This was scheduled as part of the "Thrill the World" zombie walk.

On 25 May 2008, Brisbane set an unofficial record with over 1,500 participants. In 2009, another unofficial record was set, with over 5,000 participants. In 2010, the Brisbane Zombie Walk attracted a staggering 10,000 participants to actively join in the walk and raised $13,000 for the Brain Foundation. In 2011, the aim was to continue to raise in excess of $10,000 for the Brain Foundation and to officially break the Guinness World Record for the largest Zombie Walk attendance.

That day we joined the zombie walk in Brisbane pic.twitter.com/LuEGLyq21Z

— Charlotteʕ •ᴥ•ʔ (@Charlotte___Z) November 6, 2016

The world record for the biggest zombie gathering was 4,093, set in the U.S. city of Pittsburgh. In Brisbane, they stopped counting at 8,000, which made it, at least unofficially, the biggest Zombie Walk in the world. 2012 saw the largest and the most successful Zombie Walk in the world with the event taking a whole new direction by an inclusion of a full music festival. As a result, over $55,000 for the Brain Foundation was raised.

One of Brisbane’s great traditions has been taking to the streets to express dissatisfaction with current political decisions, or even just expressing themselves. Fifty years on from the "Big March" from University of Queensland, the right to demonstrate continues to be "a simple case of freedom".

You can follow history editor Dr Glenn Davies on Twitter @DrGlennDavies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Monthly Donation

Single Donation

March on! Subscribe to IA.