Reserve Bank Governor, Philip Lowe, has triggered a massive but largely over-simplified debate on the impact of immigration on wages.

Once again, the usual suspects have taken their positions without providing a shred of actual new evidence or analysis.

Some in the media decided to put some extra spice into what Lowe said – which was actually quite balanced but without any actual analysis of the immigration trends and composition – with the headline 'Immigration levels helped keep wages low for years: RBA Governor'.

Lowe starts by highlighting that wage growth in Australia fell sharply from around 4% in 2012 to around 2% or less since 2016. Throughout this time, the RBA had significantly overestimated wage growth.

Was Lowe using immigration to make excuses for the RBA’s consistent forecasting misses?

By drawing attention to immigration, Lowe enabled the media to ignore two much more significant drivers of low wages.

Wage growth measured as labour compensation per hour worked has slowed significantly since the developed world collectively entered its "demographic burden" phase. That is, when the working-age population as a portion of total population peaked and went into decline from around 2008-2010.

This has been the case in both countries with high immigration such as Australia, the USA and Canada as well as in countries with comparatively little immigration, such as most countries in Western and Eastern Europe. Indeed, much of Europe’s immigration has been from Eastern Europe to Western Europe.

Japan, the most aged nation on the planet, and one with minimal immigration until relatively recently, has had low wage growth for almost 30 years — ever since its working-age to population ratio has been declining and its median age rising. Japan’s median age is now approaching an unprecedented 50 years of age and will shoot well past 50 over the next decade.

Some of the research anticipated that labour shortages, due to population ageing, would lead to a wages breakout. But it seems low wage growth and population ageing are actually co-travellers due to ageing reducing private consumption expenditure resulting in weak business investment.

The other factor impacting wage growth that Lowe did not mention was the Coalition Government's policy to deliberately keep wage growth low.

Policies such as caps on public sector wages; cutting of penalty rates; industrial relations reforms to strengthen the hand of employers in wage bargaining; increased casualisation of the workforce; keeping a lid on the minimum wage; and the Government continuing to largely ignore rampant wage theft are all part of this project.

While Lowe made no reference to ageing or Government wage policy in his recent speech, he did make three key points:

- There has been a strong rise in labour participation since around 2014;

- The ability of firms to tap into overseas labour markets when workers are in short supply in Australia; and

- The trend rise in underemployment.

Labour participation rates in Australia

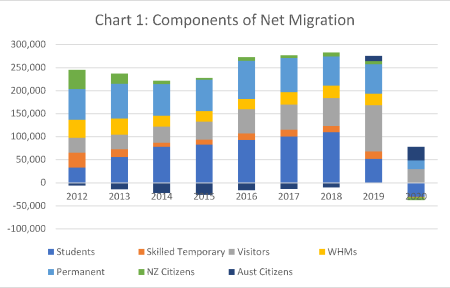

The rise in the participation rate to record levels has indeed been substantially driven by increased net migration, particularly students until 2018, as well as visitors changing status after arrival as part of the biggest labour trafficking scam in Australia’s history (see chart one).

The permanent migration program actually fell from 2014 onwards as well as an increasing portion of the program being sourced from people already in Australia. The humanitarian program was also significantly reduced in size after the one-off Syrian refugee intake in 2016.

Offsetting the impact of increased net migration on the participation rate has been the strong rise in the number of retirees in Australia. Since, 2008-09, this has increased by over a million to 3.9 million in 2018-19. This is projected to increase by another 500,000 over the next five years, thus putting downward pressure on participation.

Over the last decade, immigration has been more than replacing Australians retiring from the workforce.

Accessing overseas labour markets

Lowe is right to say that Australian employers have been able to "tap" overseas labour markets for skilled workers through skilled employer-sponsored visas. However, the contribution of these visas to net migration peaked at 32,520 in 2012 (ie when wage growth was around 4%) and has been significantly below that level ever since (see chart one).

In 2012, the unemployment rate was comparatively low (around 5%) and wage growth was close to 4%. In fact, wage growth in Australia has not been anywhere near the 2012 level ever since.

If Lowe was right that these visas contribute to lower wage growth, wages should have increased since 2012, not decreased.

Working holidaymaker visas have also fallen since 2012 as has the net movement of New Zealand citizens who also have full work rights. The negative contribution of Australian citizens leaving Australia has reduced, since peaking in the Abbott Government years of 2014 and 2015. In 2019 and 2020, the net movement of Australian citizens was positive for the first time in decades and would have helped increase participation.

But the big drivers of net migration since 2012 have been students and visitors changing status.

The student contribution to net migration increased from 32,740 in 2012 to 109,320 in 2018 before declining in 2019 to 51,840 and negative 30,700 in 2020. This also contributed to a steady increase in the number of temporary graduate visa holders in Australia to around 100,000 by the start of 2020.

Until recently, students have had the right to work for up to 40 hours per fortnight while classes are in session and full time during vacations. Most students tend to work in low skill occupations, including in hospitality, security, cleaning and so on.

These are generally minimum wage occupations with wage levels determined by the Fair Work Commission rather than by the market. It is the case, however, that many students are subject to significant wage theft with wages paid well below the legally regulated minimum. If this is the case, it will only be exacerbated by the recent decision by Immigration Minister Alex Hawke to allow students to work as many hours as they wish in tourism and hospitality jobs.

The other major contributor to the increase in net migration was visitor visa holders changing status after arrival. These increased from 32,380 in 2012 to an astonishing 100,280 in 2019. These would have been driven mainly by an increase in family visitors extending stay in Australia – but these people would mainly not have had work rights – and visitors applying for asylum to enable the undertaking of farm work.

Asylum seekers would generally have work rights until their application is decided at both the primary level and at the AAT. While these workers are, in theory, also required to be paid at least the minimum wage, many would not be paid at this rate, especially once they lose work rights after being refused at the AAT.

A rise in underemployment

Lowe notes that the increase in underemployment in Australia started around the time of the 1990 recession, when net migration fell to below 50,000. While students and other visa holders work extensively in industries with a high levels of casualisation and part-time work, the rise in these types of work are not so much a function of immigration but changes to Australia’s industrial relations arrangements, as well as the decline in the power of unions.

While it could be argued students, temporary graduates and asylum seekers have been putting downward pressure on wages of low skill workers, because they are so readily exploited and paid below minimum wages, it is far more likely that Australia’s slow wage growth since 2012 has been driven by a combination of population ageing and the Government's wages and industrial relations policy.

But for the media, it is of course much easier to scapegoat immigrants.

It sells papers and secures clicks.

Dr Abul Rizvi is an Independent Australia columnist and a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration. You can follow Abul on Twitter @RizviAbul.

Related Articles

- Federal Government's 'Intergenerational Report' based on a fallacy

- Grattan Institute's first report on skilled permanent migration like the curate's egg

- No opposition to post-COVID mass migration plan

- ABUL RIZVI: Using immigration to manage Australia's ageing population

- ABUL RIZVI: Visa processing paralysis

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.