Sometimes our articles provoke fierce debate, such as this April piece by Thomas Bee about the media and racism, which was read close to 50,000 times.

*****

Waleed Aly's refusal to apologise for an interview with former AFL Collingwood player Héritier Lumumba is pivotal in preserving freedom of the press, writes Thomas Bee.

IN 1897, OSCAR WILDE declared: ‘Yet each man [or woman] kills the thing he loves.'

And, in a pseudo-puritan society, by silencing thought outside the progressive orthodoxy but praising Cardi B’s salacious performance of 'WAP' at the Grammys, we are at risk of losing key societal pillars — justice and forgiveness. For this reason, writer, lawyer and Channel 10 broadcaster Waleed Aly’s resolute refusal to bow down to mob rule, is more important than we think.

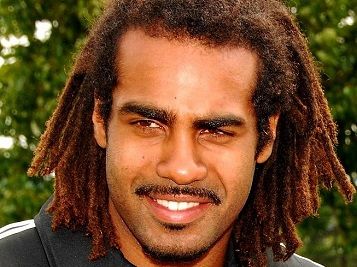

In recent weeks, Waleed Aly has faced increasing pressure to apologise for a 2017 interview with former Australian Football League (AFL) Collingwood player Héritier Lumumba. In the ostensibly infamous exchange – which aired on The Project – Aly, along with fellow panellist, Peter Helliar, appeared to question the legitimacy of Lumumba’s allegations of systemic racism within the Collingwood Football Club.

Controversial at the time, outrage has resurfaced following the recent findings of Collingwood’s 'Do Better' report vindicating Lumumba’s claims of racial abuse. The disgust expressed by some Twitter users led to Peter Helliar taking to Twitter to apologise and Channel 10 has removed the interview.

Despite pressure from the public and the actions of Aly's colleague and his employer, Aly has refused to say sorry. This is pivotal in preserving the foundations of journalism because de-platforming Aly or forcing him to apologise would set a dangerous precedent.

In a literal sense, we would be expecting Aly to say sorry for doing his job. Creating a disincentive for journalists to ask questions, seek truth and hold people to account is a backward step for a democratic society. It is paramount we foster conditions where the press is free to pursue truth — no matter what the situation.

This is yet another example of the cult of victimhood, where some undoubtedly believe any accusation that suits the narrative. In this situation, Lumumba’s experience of racism may have been proven to be true, but this does not make Aly’s questions any less valid. If they were, it would delegitimise the Fourth Estate — a fundamental institution for any democracy.

Not only can this have a terrible impact on the standard of journalism but, coupled with "cancel culture", it can cripple the judicial process and society’s propensity to forgive. While it is important we strive to remove racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and any other form of discrimination, it is critical it does not come at the cost of eroding the universal tenets Western civilisation is built upon.

To arbitrarily declare someone an "enemy of the state" and destroy their life has all the hallmarks of totalitarianism — a political system associated with some of the cruellest living conditions in history.

A recent example of this finger-pointing occurred at Teen Vogue in America, where Alexi McCammond was forced to resign as editor before even starting. The 2019 National Association of Black Journalists' (NABJ) Emerging Talent was denied this position of influence after more than 20 staffers wrote to management, some posting their complaints on social media.

The uproar was sparked by offensive tweets McCammond had made over a decade ago when she was a teenager; at least two advertisers also threatened to end their affiliation with the publication. This was despite the fact McCammond was transparent about the tweets with Teen Vogue and had deleted them and apologised back in 2019 when they were first brought to light.

These events are reflective of the bloodthirsty beast cancel culture can become. In this instance, the consequence was a woman of colour losing her high-powered position and having her reputation forever tarnished. Can we expect this to become a regular occurrence?

The problem with giving in to this form of social media vigilantism is that it can be a very slippery slope to go down and, in this case, one that appears to have had no brakes, let alone a stop button. McCammond had already been publicly shamed for her tweets and apologised, but still lost her job in spite of all the good she may have done for minorities over the years.

Standardising "cancel culture" means we would be living in a graceless society where we may as well have any stupid comment we have ever made tattooed on our forehead. The analogy may seem extreme, but it is where this kind of normative can lead.

The closest thing to cancel culture we have seen in Western society was during the (U.S. Senator) McCarthy era in the 1950s — thankfully, it was quickly put to bed. This new phenomenon is terrifying because it hides behind a veil of righteousness and virtue, perhaps making it an even tougher foe than McCarthyism ever was.

We must demand a higher standard of each other but cannot allow Wilde’s lament to become a truism.

Thomas Bee is a journalism graduate who works in corporate affairs and public relations. As a side hustle, he doubles up as a freelance writer and is passionate about Australian politics.

Related Articles

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.