In 1918, as the First World War came to a close, 260,000 Australians had to be repatriated. The returning troops brought with them the “Spanish” influenza, a deadly pandemic that swept the world in 1918–19. As a result, many men had to be quarantined before being reunited with their families.

However, many Australian soldiers would never have survived quarantine without the care and sacrifice from nurses such as Sister Rosa O’Kane, writes history editor Dr Glenn Davies.

WAR HAD LOST its patriotic glow by 1918. The excitement of adventure had worn off and horror, distrust and a deep sadness replaced it. Many women wore black, newspapers continued to print lists of the Australian dead and a visit from a church minister was loathed as he often brought news of the death of a loved one.

The 1918–1919 influenza pandemic stands as one of the greatest natural disasters of all time. In a little over a year, the disease affected hundreds of millions of people and killed between 50 and 100 million — at least three times more than the deaths caused by the First World War. Few families or communities escaped its effects and possibly 25–30% of the world’s population was infected with influenza in 1918–1919.

While its exact origins are still debated, it’s understood that the “Spanish Flu” did not come from Spain. The name seems to have arisen as reporting about influenza cases was censored in war-affected countries, but Spain was neutral, so frequent stories appeared about the deadly flu in Spain.

It’s unlikely that the Spanish Flu changed the outcome of World War I, because combatants on both sides of the battlefield were relatively equally affected. However, there is little doubt that the war profoundly influenced the course of the pandemic. Concentrating millions of troops created ideal circumstances for the development of more aggressive strains of the virus and its spread around the globe.

Ever since the first military nurses sailed for the Boer War in South Africa in January 1900, Australian nurses have served in theatres of war and conflict around the world. During the First World War, 2,139 nurses served with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and 130 Australian women served with Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) or contributed to the war effort overseas through associations like the British, French or Belgian Red Cross or the Young Women’s Christian Association.

Australian nurses served in the Mediterranean, France, Belgium, England, Salonika and India as well as on hospital ships. On the Western Front, they worked in advanced dressing stations and field hospitals behind the lines, often within range of artillery and subject to aerial bombardment. However, by the end of the First World War, 23 of these women had died in service.

The Spanish Flu made landfall in Australia in January 1919 and resulted in about a third of all Australians becoming infected and nearly 15,000 people being dead in under a year. These figures match the average annual death rate for the Australian Imperial Force throughout 1914–18. More than 5,000 marriages were affected by the loss of a partner and over 5,000 children lost one or both parents. In 1919, almost 40% of Sydney’s population had influenza, more than 4,000 people died and in some parts of Sydney influenza deaths comprised up to 50% of all deaths.

It wasn’t just victims who were affected. Across Australia, regulations intended to reduce the spread and impact of the pandemic caused profound disruption. The nation’s quarantine system held back Spanish Flu for several months, meaning that a less deadly version came ashore in 1919. But it caused delay and resentment for the 180,000 soldiers, nurses and partners who returned home by sea that year.

Arguably, 1919 could be considered as another year of war, albeit against a new enemy. Indeed, the typical victims had similar profiles: fit, young adults aged 20-40. Unlike other influenza pandemics, which mainly impacted on people at the extremes of life, the 1918–1919 outbreak infected mainly young, healthy adults in the prime of life. This is known as a cytokine storm because young people’s strong immune systems reacted so well that it killed them.

Whatever your heritage, your ancestors and their communities were almost certainly touched by the pandemic. It’s a part of all of our family histories and many local histories. And yet, little is known of its generational impact.

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19 creates a framework for a fascinating event around health care coming up at @AugieCWS: https://t.co/QXrlGaMZNh pic.twitter.com/jts7CYBYcl

— SF Biz (@bizsiouxfalls) April 18, 2019

Despite the disruption, fear and substantial personal risk posed by the Spanish Flu, tens of thousands of ordinary Australians rose to the challenge. The wartime spirit of volunteering and community service saw church groups, civic leaders, council workers, teachers, nurses and organisations such as the Red Cross step up.

They staffed relief depots and emergency hospitals, delivered comforts from pyjamas to soup and cared for victims who were critically ill or convalescent. A substantial proportion of these courageous carers were women, at a time when many were being commanded to hand back their wartime jobs to returning servicemen.

The 1,200 troops on board HMAT Boonah were bound for the trenches of the Western Front in World War One. But it wasn't the battlefields of Europe that claimed dozens of their young lives, instead meeting their fate with Spanish influenza in Perth's southern suburbs. It was the last troop ship to leave Australia bound for Europe, but the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918 before HMAT Boonah reached the Western Front.

Three days later, it docked in Durban, South Africa, to re-coal before heading back to Australia. Although the Aussie troops weren't allowed to go to shore in Durban, they mingled with local men re-coaling the ship to buy ostrich feathers as souvenirs. This encounter proved to be a deadly mistake for dozens on board, who became infected by influenza. This spread among the troops, resulting in more than 300 cases.

By the time the troopship reached the shores of Fremantle on 7 December 1918, 400 of the 1,000 men on board were infected. The HMAT Boonah wasn't allowed to dock and was left stranded in Gage Roads, with the hundreds of infected men taken to the Woodman Point Quarantine Station. With no medical staff to care for the men, authorities desperately turned to a ship of military nurses on board SS Wyreema, also on its way back to Australia.

Second Lieutenant Sister Rosa O’Kane was born in Charters Towers on 14 April 1890. She was the daughter of John Gregory O’Kane and Jeanie Elizabeth O’Kane and grand-daughter of the former owner of the Northern Miner, Thadeus O’Kane. Rosa trained as a nurse in the Townsville Hospital which she completed in 1915. She then worked in Charters Towers and Hughenden before being appointed Matron at the Winton Hospital in 1917.

During this time she received notice from the military authorities that she may need to take up duties in Brisbane. She was subsequently called up for duty on 27 November 1917 and worked at the military hospital in Kangaroo Point. In June 1918, O’Kane sent a telegram to her mother stating she was leaving immediately on a transport ship and expected to be back in six months.

It's been 100 years since the Spanish flu hit Parramatta which closed schools and businesses, crowded hospitals and masks became compulsory in public. Take a trip down memory lane and see how far we've come since the deadly strain hit Western Sydney. #flu https://t.co/E2SnvWCzjn

— West Sydney Health (@WestSydHealth) April 16, 2019

O’Kane embarked on the troopship SS Wyreema from Sydney on 14 October 1918 with a party of 40 Australian army nursing sisters bound for Thessalonica (Salonika). They had already reached Cape Town when Armistice was declared on 11 November 1918. As a result, the SS Wyreema arrived back at Fremantle on 10 December 1918.

Rosa O’Kane was selected as one of the 20 volunteers to tend the infected soldiers. By this time, the effects of the worldwide influenza epidemic were being felt. The volunteers from the nurses aboard the SS Wyreema worked at the Quarantine Station Hospital tending to infected returning soldiers. Of the 20 nurses from the SS Wyreema who volunteered to care for the infected soldiers, 15 contracted Spanish Flu and four made the supreme sacrifice — Army staff nurses Rosa O’Kane, Doris Ridgway and Ada Thompson and civilian nurse Hilda Williams. The tragedy also claimed the lives of 26 soldiers.

On Anzac Day, 25 April 1933, a touching picture was conveyed in The West Australian from one of the quarantine sisters, describing the burial of Sister O’Kane:

Between 2 A.M. and 3 A.M. on a beautiful moonlight night, writes Sister Morris, four sailors carried the body (wrapped in a winding sheet of the Union Jack) to the mortuary out in the scrub. Later in the day the burial took place at the quarantine station. The nurses made little wreaths from West Australian wild flowers, which were placed on the coffin with the Union Jack. I did not leave the grave side till the “Last Post” was sounded… Let us, then, on Anzac Day, think for a moment of that lonely little cemetery in the bush and those white sanded graves lying in the sunlight in the sound of the murmuring sea.The Weekly Times, on 28 December 1918, announced Sister Rosa O’Kane’s death:

Sister Rosa O'Kane, whose death is reported from Perth through influenza, left Victoria about eight weeks ago on a transport for “service somewhere.” On the voyage a wireless message was received from the military authorities in South Africa, calling for volunteers to nurse influenza patients in quarantine. In responding to the call of duty, Sister O'Kane made the supreme sacrifice.And the Catholic Press, 16 January 1919, wrote:

General regret was expressed in Townsville, when it became known that Sister Rosa O'Kane Had made the supreme sacrifice, dying from the effects of that dread scourge, Spanish influenza, whilst nursing the soldier patients at Woodman's Point.

Most of the dead were buried at Woodman Point, including the four nurses. In 1920, Ada Thompson was exhumed and re-interred at Fremantle Cemetery. Most other service personnel were exhumed from Woodman Point’s bushland cemetery in 1958 and re-interred at Perth War Cemetery.

The death of Rosa O’Kane 100 years ago prompted her home town of Charters Towers in north Queensland to fund a monument to her thousands of kilometres away to the south of Fremantle in Western Australia that embodied all who died in the Great World War. As demonstrated by the monument, Rosa O’Kane was much loved and greatly missed by her family and friends in Charters Towers. Her sacrifice was remembered and held true in particular by her mother, Jeanie O’Kane.

Her obituary stated:

From that moment in 1919 until the day of her death, Mrs O’Kane was in every respect a ‘war mother’ and no cause was ever so dear to her as that of the digger or the nursing sister. As each year passed she was an outstanding personality among those who organised the annual dinner (luncheon) in honour of soldiers on Anzac Day, and the aim or unanimity in public commemoration of Anzac Day was an objective for which she was an unceasing champion.

Jeanie O’Kane had three children – two sons and her daughter Rosa – before being widowed at an early age. To support them, she took over the family newspaper that had been started by her father-in-law, Thaddeus O’Kane, successfully managing it for several years until she sold the business to return to teaching.

It was uncommon for the families of women to apply for the pension as women were not generally considered to be part of the workforce and were not viewed as providers at the time. Servicemen made up the overwhelming majority of war deaths, with 60,000 losing their lives.

An extract from the National Archives World War I repatriation file of Jeanie Elizabeth O'Kane contains the widow Jeanie O'Kane's application for a war pension after the death of her only daughter, Nurse Rosa O'Kane, from the Spanish Flu. At the time it was common for a widow to receive a war pension if an unmarried son was killed during the war and the mother could show that she was a dependent. A decision needed to be made as to whether a widowed mother of a deceased and unmarried daughter should receive the same benefits.

Advice was received from the Repatriation Department stating:I want your followers to see how much you are devoted to vaccine conspiracy theories, that then are so easily refuted:

— The Woodman (@TheWoodman2) April 16, 2019

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 was caused by an experimental vaccine? A conspiracy theory I hadn't heard of before... https://t.co/ZedeCvDzRD

‘...as members of the Army Nursing Service are soldiers within the meaning of the Repatriation Act an application….may be accepted from Mrs. O'Kane.’

Jeanie O’Kane’s application was originally rejected but after she proved her dependence upon her late daughter during the 12 months before Rosa’s enlistment, her claim was reassessed and she was granted a pension of two pounds per fortnight.

The Brisbane Courier wrote on Armistice Day, 11 November 1931:

Sister O'Kane's grave, with a headstone erected by the patriotic committee of Charters Towers in memory of her magnificent self-sacrifice, is in the only military cemetery in Australia – that at Woodman's Point – and each Anzac Day a contingent of returned soldiers visits the cemetery and places wreathes on the graves of the three nurses who made the supreme sacrifice.

The WA Defence Department wanted to transfer O’Kane’s remains to Karrakatta cemetery as her story had become of great interest to the community, but her mother Jeannie O’Kane ‘would not have the remains disturbed’.

The bodies of Rosa O’Kane and Hilda Williams remain at Woodman Point rather than the Military Cemetery at Karrakatta, the former marked by an impressive granite obelisk and the latter by a simple wooden cross. In the century since 1919, the surroundings have overgrown with bushland, but the graves are maintained by the Friends of Woodman Point Recreation Camp, who have kept the Quarantine Station open to the public.

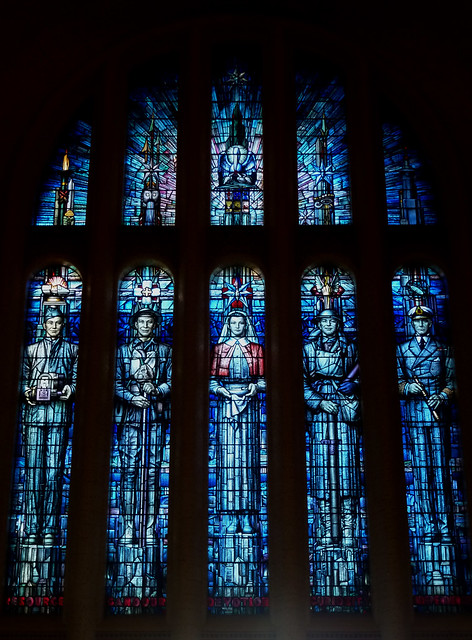

In the Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, there are 15 stained glass windows. Each shows a figure dressed in military uniform and under each figure is a word which describes a quality displayed by Australians during wartime. One window features a nurse. She represents all military nurses who have shown dedication to their patients and a commitment to catering for the sick and wounded during wartime. This window bears the word ‘Devotion’.

The actions of Sister Rosa O’Kane were not only commemorated through a monument funded by the people of Charters Towers but have also been acknowledged throughout the then British Empire.

Sisters O’Kane, Ridgway and Thompson are commemorated at the Five Sisters Window in the North Transept of York Minster. The Hobart Mercury, 20 June 1925, described how their names are inscribed on oak panels along with 1,400 other women from the British Empire who lost their lives during the First World War.

The Queenslander, 9 May 1925, reports the names of the Australian nurses who either died or were killed on active service during the war are included in a list of Dominion nurses who made the supreme sacrifice at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital for Women, London.

Rosa O’Kane is also recognised on the Maryborough Nurses Honour Board and at the Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour where her name will be projected onto the exterior of the Australian War Memorial Hall of Memory on:- Mon 22 April 2019 at 7:07 PM

- Sat 29 June 2019 at 11:21 PM

- Wed 18th Sept 2019 at 7:50 PM

By the end of 1919, the global influenza pandemic was over. 1919 had been the year of death for women. The Spanish Flu killed just as many women as men, but despite the relatively high mortality rates, the Spanish Flu faded from public awareness over the decades.

While the death rate in Australia was lower than in many other countries, the influenza pandemic was a major demographic and social tragedy, affecting the lives of many.

Jeannie Elizabeth O’Kane passed away on 6 July 1936 at the age of 77, leaving behind her two sons and their families. Until then, she had kept Rosa O’Kane’s name alive but, like the Spanish Flu pandemic, it became forgotten. In Charters Towers today, Rosa O’Kane is totally forgotten, even absent from the town cenotaph. A woman who had been acknowledged all around the British Empire for her sacrifice banished into the public silence of her hometown.

Perhaps this is because the pandemic coincided with the deaths and media focus on the First World War and due to the rapid pace of the pandemic resulted in limited media coverage. In some areas, the Spanish Flu was not reported on, with the only mention being that of advertisements for medicines claiming to cure it. Perhaps it was because a significant number of the casualties in 1919 were women.

100 years later, it’s time to restore our memories of the Spanish Flu and commemorate how communities came together to battle this unprecedented public crisis. Compared with the Anzac memorials that peppered towns and suburbs in the decades after the First World War, few monuments mark the impact of pneumonic influenza, or Spanish Flu. The Woodman Point Quarantine Station Cemetery is one of the few public heritage sites in Australia associated with the history of public health and in particular the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918-1919.

You can follow history editor Dr Glenn Davies on Twitter @DrGlennDavies. Find out more about the Australian Republican Movement HERE.

Remembering Staff Nurse Rosa O’Kane, Australian Army Nursing Service, died aged 28 on 21st December 1918: https://t.co/OrXj0ihtvO #WW1 #nurses pic.twitter.com/59QNBNflM6

— Remember the fallen (@war_fallen) December 21, 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.